The exam’s Comprehension Text

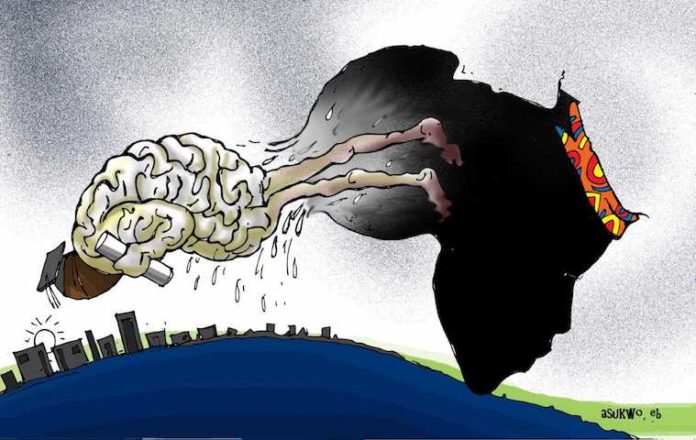

The Economic Commission for Africa estimates that between 1960 and 1989, some 127,000 highly qualified African professionals left Africa. According to the International Organization for Migration, Africa has been losing 20,000 professionals each year since 1990. This has raised claims that the continent is dying a slow death from brain drain, which has financial, institutional, and societal costs. African countries get little return from their investment in higher education, since too many graduates leave or fail to return home at the end of their studies. the United Nations has finally admitted that emigration of African professionals to the West is one of the greatest obstacles to Africa’s development.

Kofi Apraku, an African living in the US, is eager to go back home. Nearly twenty years ago, he came to America as an exchange student to finish high school. Kofi ended up staying there to get his doctorate. He achieved distinction not only in his professional career, but also in his social and personal life. Now a professor of economics at the University of North Carolina at Asheville, apraku is preparing to go back to Ghana to work with the ministry of agriculture as director and policy counselor. “The missing link for Africa’s social and economic developments,” he says, “is the African immigrant who has become educated and experienced abroad but who has not been able to go back home.”

A number of factors have kept expatriates, such as Apraku, from getting back to their Homeland. Somewhat like African refugees, African immigrants are victims of brutal governments, poverty, civil wars, poor economies, etc. According to a United Nations estimate, 100,000 trained professionals like a Apraku are working in the West. Most of them can’t – or won’t – return. The result: a devastating brain drain that has deprived the African continent of much of its top talents.

Surprisingly, some Africans are willing to return to where they belong. Despite the very low salaries, poor professional facilities and limited opportunities, they are decided to make it back home. “Africa’s development remains an African responsibility,” says Apraku. “Some of us have been lucky to get enough experience to share such a responsibility,” he continues.

Certainly, the trip back home can be hard. For instance, the average salary in African universities does not exceed $500 a month. Many of the best-paid jobs in Africa still go to foreigners. Thousands of foreign advisors in the public sector in sub-Saharan Africa are paid up to 4,000 dollars a month. It is true that these have expertise unfound in Africa, but this situation can be changed if, and only if, educated Africans are willing to sacrifice and work together for a brighter tomorrow in Africa.

National exam | Arts Stream | Ordinary Session 2008